-

Discovery Science

Immune cells strike tricky balance after fighting flu

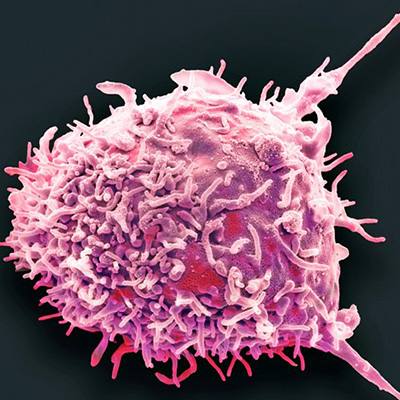

The immune system exists to fight infection, but it must also know when to rest once that infection is controlled. It’s a balancing act examined in a recent Science Immunology publication where Mayo researchers report on how one immune cell type walks this tightrope after fighting the flu.

After infection, the immune system produces cells that remember the disease so the body can fight it faster the next time we’re exposed. Most of these “memory T-cells” patrol throughout the body, but some “resident memory T-cells” wait in the organ where the infection occurred. Typically, these cells act as extra reinforcements where they’re needed most, but when the disease is the flu, the process is complicated. The influenza virus leaves behind pieces of itself in the patient’s lungs, long after the patient has recovered.

Those pieces keep stimulating these resident memory T-cells. Too much immune system activity can damage nearby tissues, so how do these cells keep from harming the lung?

“They enter an ‘exhausted-like’ state,” says senior researcher of the study, Mayo immunologist Jie Sun, Ph.D. “They can still function like normal memory T-cells and mount a rapid immune response, but they also respond to inhibitory signals, which keep them from damaging lung tissue. It’s a delicate balance.”

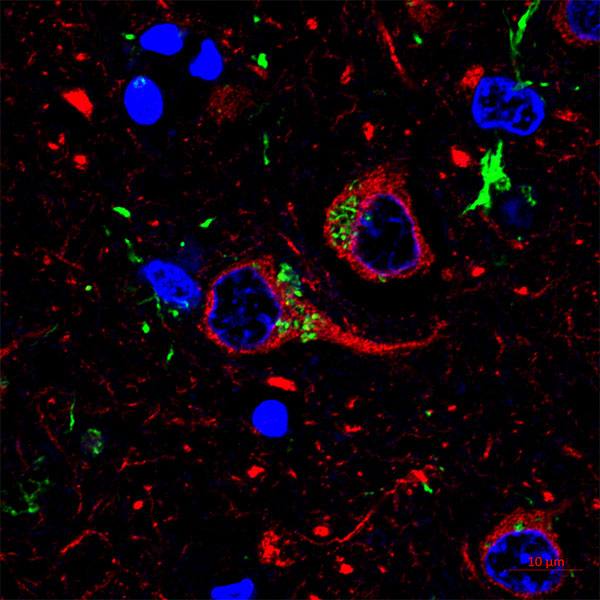

While normal memory T-cells completely lose functionality when they are exhausted, these “exhausted-like” cells do not. The authors show that although these cells have many characteristics of exhausted cells, they can still respond to re-infection. They also suggest that the receptor PD-1, which inhibits T-cell function, is the fulcrum of this balancing act. When the authors blocked PD-1 in mice previously infected with influenza, the mice responded faster and more robustly against a second infection. However, the mice also developed early signs of lung fibrosis.

While blocking PD-1 ensured that T-cells were vigorous during reinfection, it also blocked the signals that stop the immune cell response when it’s gone too far. As anti-PD-1 drugs have become more common to treat cancer, the authors write that this study suggests cautious use for patients with lung disease.

This study was performed in collaboration with researchers from the Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, the University of Texas Health Science Center, Emory University School of Medicine, and Indiana University School of Medicine. It was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Huvis Foundation, the Cancer Research Institute, Mayo Clinic Roger and Arlene Kogod Center, and Mayo Clinic Center for Biomedical Discovery.