-

Discovery Science

Supporting the Lives of Those Who Change Lives

Joline E. Brandenburg, M.D., devotes her workday at Mayo Clinic to treating children with cerebral palsy. At home, she cares for her 11-year-old daughter, who also has the condition. In between, Dr. Brandenburg conducts groundbreaking research that ultimately might ease the effects of the movement disorder or even prevent it. Scientific research at a level that changes lives takes time — which is in short supply when you’re also a caregiver. In the juggling act of a clinician-researcher's life, the ball that generally gets dropped is research.

“A lot of grant writing and data analysis happens outside clinic hours, in the evening and on weekends,” Dr. Brandenburg says. “When you have a child with special needs, you don’t have that flexibility.”

Dr. Brandenburg is among the recipients of a grant from Mayo Clinic’s Office of Research Diversity and Inclusion that seeks to foster the careers of researchers who are also primary caregivers. The $25,000 awards are used to directly fund aspects of a project or offset clinical hours, freeing the recipients to conduct research during the workday. Mayo Clinic initially planned to award two grants. Due to the number of applicants, eight were given.

“This is an institutional investment,” says Gregory Gores, M.D., Executive Dean of Research. “We are committed to fostering research that ultimately changes the practice of medicine.”

“We recognize that caregivers experience many challenges, and we want them to succeed. These funds can provide additional resources to complete or advance research projects,” says Jennifer Westendorf, Ph.D., who directs Mayo Clinic's Office of Research Diversity and Inclusion. “This support for investigators who have a lot of responsibility in their lives demonstrates our understanding and respect for what they’re doing.”

The grant recipients’ projects encompass a range of pressing medical issues, including doctor-patient communication, concussions in young athletes and the cardiovascular and metabolic risks for transgender individuals who have hormone therapy. The scientists’ caretaking responsibilities are equally diverse. Here are some of their stories.

Helping Kids Move, Breathe

Dr. Brandenburg’s interest in cerebral palsy began during her medical training, when she often cared for children with the condition. “I grew to love the resilience of those kiddos and their families,” she says. After meeting parents who adopted children with cerebral palsy, Dr. Brandenburg was inspired to do so, too.

Now Dr. Brandenburg’s daughter is busy with sled hockey, horseback riding and Girl Scouts, in addition to school and medical appointments. These activities require physical support, which Dr. Brandenburg provides along with her daughter’s father and stepfather. “Managing schedules is my forte,” Dr. Brandenburg says.

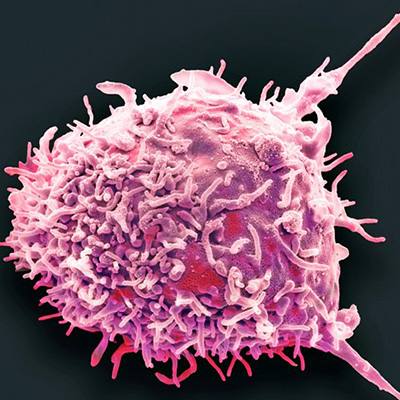

Cerebral palsy’s effect on functional abilities varies greatly among individuals, and the condition’s precise cause is unclear. Most research focuses on the brain. But Dr. Brandenburg is looking at the spinal cord — specifically, motor neurons, the cells that stimulate nerves to make muscles move.

“If the motor neurons aren’t functioning properly, the muscles can’t do their job,” she says.

Dr. Brandenburg’s hypothesis is that disruption in the development of the spinal cord plays a role in causing cerebral palsy. To investigate that idea, she and colleagues examine the spinal cords of laboratory mice that have the same increased muscle excitability seen in individuals with cerebral palsy.

“If we can sort out when and how the disruption occurs, we can think about interventions to prevent that process, such as medications that protect the motor neurons during spinal cord development,” she says.

The research-career advancement award supports Dr. Brandenburg’s current project — a study of the mechanisms underlying breathing problems in spastic cerebral palsy. The grant also helps maintain important research models while Dr. Brandenburg applies for long-term funding through the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

“The Mayo grant gives me time to work on an award that can greatly increase our understanding of cerebral palsy,” she says. “If we can find an intervention to reduce the severity of the movement problems and the breathing difficulties for these kids, we can impact their lives tremendously.”

Smarter communication to improve cancer treatment

When Carrie A. Thompson, M.D.,started her career, she received a prestigious NIH award, known as a K12, to jump-start her research alongside her clinical practice. Dr. Thompson was studying survivorship in people with lymphoma, a blood-system cancer. Dr. Thompson and her husband, also a Mayo Clinic physician, had a young daughter. Within a few months, Dr. Thompson discovered she was pregnant with twins. She subsequently had to spend three months on bed rest before taking a three-month maternity leave. This meant that her grant was in jeopardy, since renewal of K12 funding depends on a researcher’s productivity in the initial year.

“Life was crazy busy. Despite my best efforts, I lost the K12,” Dr. Thompson says. “Although I understood why, it was devastating.”

Since then, Dr. Thompson has acquired other funding for her research. But with a 10-year-old and 8-year-old twins, time remains a challenge. “My husband and I have made the choice that unless we are scheduled to work in the hospital, we spend weekends at home with our family,” she says. “The grant allows me to do research during the regular workday.”

Dr. Thompson’s research involves patients’ use of mobile technology to communicate with doctors after cancer treatments. The goal is to get information about patients’ symptoms and quality of life to clinicians in real time, to better manage therapy.

“We know that opening up communication improves patient outcomes. Symptoms are better managed, hospitalization and emergency room visits are reduced, and overall patient survival increases,” Dr. Thompson says. “Better symptom management might allow patients to stay on chemotherapy longer and avoid dosage reductions.”

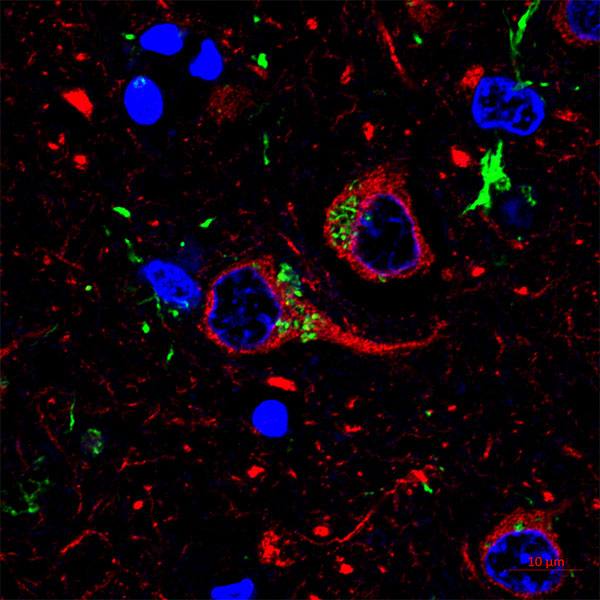

The Mayo Clinic grant helps finance Dr. Thompson's current project evaluating patients’ reactions to the cutting-edge cancer treatment known as CAR-T cell therapy. That therapy involves genetically modifying an individual’s immune cells so they can identify and kill cancer. Although CAR-T cell therapy shows promise for people with recurrent blood cancer, the side effects are generally severe. Study participants will report their symptoms and quality of life via questionnaires on a mobile phone or tablet. An additional patient self-assessment will utilize emoji faces, which Dr. Thompson has used in previous studies of people undergoing chemotherapy. Real-time communication is key. Patients who see their doctors every three weeks between treatments might not recall the severity of their symptoms once they’re resolved. Or patients might tough it out so their treatment isn’t cut back.

“If doctors get the information when the patient is actually experiencing the symptoms, we have the opportunity to intervene,” Dr. Thompson says. “This isn’t about trying to reduce the interaction between patients and health care providers. We’re trying to make that interaction smarter and more patient-focused. We want to harness the power of technology to improve patient care.”

Safeguarding young athletes’ brains

The only time Jennifer Wethe, Ph.D., recalls becoming emotional while writing a cover letter was when she applied for the Mayo Clinic research-career advancement award. As co-director and lead neuropsychologist for Mayo Clinic’s concussion program in Arizona, Dr. Wethe works to protect the brains of young athletes. She is also a single mother of two children, ages 10 and 14, who have special needs, and previously helped care for family members with a neurodegenerative condition.

“This is the most meaningful grant I have ever gotten,” she says. “It’s the gift of time — four or five hours a week I can spend on research. That’s been tremendously helpful for getting our project off the ground.”

That project is the Mayo Clinic Concussion Check Protocol, which can determine when a youngster should be removed from play and assessed for a possible concussion. Although brain injuries in professional athletes have been well publicized, less attention has focused on young people — whose developing brains are most vulnerable to the long-term effects of head hits.

“On the youth level, where the vast majority of sports is played, there’s nobody on the sidelines whose job is to look for neurologic injury,” Dr. Wethe says. “The ‘When in doubt, take them out’ mantra is the equivalent of putting the back of your hand on a kid’s forehead to check for fever. It isn’t an objective measure, and it’s anxiety-provoking for parents and athletes.”

The Concussion Check Protocol can be used on the sidelines by a designated adult safety officer. It entails watching for concerning hits or signs of concussion, assessing symptoms, asking a few orientation questions and conducting a brief eye movement test. Athletes who fail any of the steps should be removed from play until cleared by a medical professional.

“We reassure parents that they’re not making a diagnosis of concussion. They’re just deciding whether a kid should be removed from play until assessed by a professional,” Dr. Wethe says. “The analogy is, ‘My kid has a fever. I don’t know why, but I’m taking her to a doctor.’”

Since validating the protocol, Dr. Wethe has devoted hours to teaching it to youth sports leagues. The grant provides time for developing an online training program to make the protocol more widely available, as well as analyzing and publishing data about the protocol.

“This is highly translational research that directly impacts a lot of lives,” she says. “It takes time and legwork, and the project wouldn’t be nearly as far along without the grant.”

Challenging conventional wisdom in transgender care

Mayo Clinic’s commitment to diversity encompasses medical staff as well as patients . As research director of the Mayo Clinic Transgender and Intersex Specialty Care Clinic, Alice Chang, M.D., works to increase understanding of the health status of sexual and gender minorities. Mayo Clinic is one of the few centers in the United States to offer multidisciplinary transgender care and gender-affirming surgeries.

Dr. Chang's current focus is how sex-hormone therapy affects cardiovascular and metabolic health. Since joining Mayo Clinic six years ago, she has also been the primary caregiver for her 15-year-old son, as her husband was unable to leave his academic position in another state.

“I don’t think I realized how much research has to happen outside normal work hours. My ‘second shift’ at home has significantly limited me in moving my project forward,” Dr. Chang says.

Her investigation of fat tissue and transgender hormone therapy has the potential to change the approach to transgender care. Gender dysphoria treatment includes feminizing and masculinizing hormone therapy. For transwomen, feminizing hormone therapy suppresses testosterone production while also supplying estradiol, the major type of female sex hormone.

Concern over the effects of lower testosterone in transwomen has grown, following studies demonstrating greater cardiovascular risk for transwomen than age-matched men. Indeed, cardiovascular disease is the second leading cause of death for transwomen.

The conventional wisdom is that low testosterone is likely responsible. But that’s challenged by recent studies showing that transwomen who opted for gonadectomy, or surgical removal of their testes, actually had better metabolic health than transwomen who retained their testes.

“You would think that removing testicles would further lower testosterone and cause more cardiovascular and metabolic problems,” Dr. Chang says. “In fact, studies have shown the opposite — after gonadectomy, transwomen had less liver fat and improved insulin sensitivity.”

Dr. Chang hypothesizes that fat storage and insulin sensitivity are determined by the ratio of sex hormones, not the presence or absence of hormone-producing ovaries or testes. To test that hypothesis, she and colleagues are measuring insulin sensitivity, body composition and fatty acid metabolism in transwomen and transmen. The researchers are taking those measurements before and three months after the start of sex-hormone therapy, and before and after surgery for transgender individuals who opt for gonadectomy.

The results can help guide transgender care, particularly the risks and benefits of gender-affirming therapies. “If gonadectomy could be beneficial, that would raise questions about how we approach surgery and other hormone-suppressing medications such as GnRH agonists,” Dr. Chang says. “But on the other hand, if it’s the ratio of sex hormones that’s important, we can determine a target ratio and adjust therapy accordingly.”

She notes that the study’s findings about the effects of the sex hormone ratio can also inform the treatment of postmenopausal women and men with testosterone deficiency. “This research is going to close some loops. We know that estradiol is equally important for men and women in terms of bone health, but we don’t know about cardiovascular health,” Dr. Chang says. “The Mayo Clinic grant has exponentially increased the ability to move this project forward.”

Building the workforce of the future

A recent article in Nature, reported that nearly half of female researchers leave scientific fields due to family responsibilities. “We want to bridge the gap so that our researchers can continue to advance their careers," Dr. Gores says. “Our goal is to improve the workplace climate and ensure that we continue to nurture talent for years to come.”

- Barbara Toman, July 2019