-

Biotherapeutics

Discovery’s Edge: Hope For Healing With Regenerative Medicine

Crohn's-related wounds may have met their match in a pioneering regenerative therapy thanks to truly collaborative team science

In the world of medical trials, a two-year follow-up period requiring MRIs, phone calls and multiple doctor visits would turn off many potential participants.

But those interested in the phase I regenerative medicine trial led by Mayo Clinic gastroenterologist William Faubion, M.D., are all too happy to comply. The research team is testing the use of stem cells derived from the patient's own body to heal open wounds caused by Crohn's disease. Called perianal fistulas, these wounds are holes leading from the inside of the rectum to the outside of the body, near the anus.

In Crohn's patients, a fistula develops when the characteristic inflammation in the digestive tract is so great that an ulcer forms, spreads through the intestinal wall and then bores a hole through muscle and skin near the anus. Crohn's disease is chronic and has no known cure. It afflicts up to 700,000 Americans, according to the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America.

Often perinatal fistulae resist treatment, both with medications and through treatment with a seton, a thread that is placed to promote drainage and healing. Currently standard therapies work less than half the time. Even when they do work, fistulae often return.

Without long-term healing the situation gets worse, with fecal leakage, abscesses, more fistulae and possible cancer. Surgery can provide some relief, but worst cases result in removal of the rectum and use of a permanent stoma and colostomy bag.

Compared to these realities, a two-year follow up clinical trial is a welcome alternative.

“The patient response has been dramatic, I would say,” notes Eric Dozois, M.D., colorectal surgeon and researcher at Mayo Clinic in Minnesota who performs the procedures involved in the trial. “Patients are flying from all over the country to hopefully be involved with this trial. These are patients that have struggled. They’ve had multiple procedures. They can’t get their fistulas to heal.”

Dr. Faubion and the team have enrolled more than half of the 20 patients they plan to recruit.

The trial, which has been supported by The Richard M. Schulze Family Foundation and Jerry and Connie Ehrlich, centers around a patient’s own mesenchymal stem cells found within the body’s fat stores. These cells can grow into one of several types of skeletal tissue, such as bone, cartilage, fat or muscle. They’re also integral to the body’s healing process.

Each trial participant receives therapy as needed for any existing infection in the fistula, and general treatment for Crohn’s disease. Following that, Dr. Dozois performs a minor operation to examine the fistula tract and also to remove a small sample of fat from the patient’s abdomen.

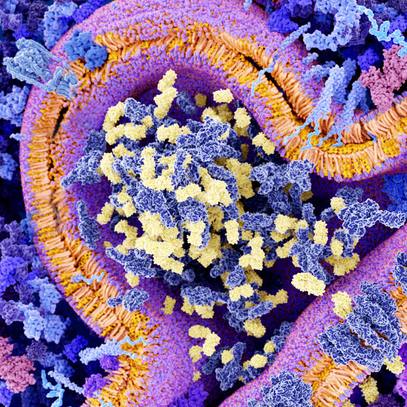

Inset – a close-up of the one of the six “legs’ that make up the fistula plug. The cells adhere to the matrix and are delivered to the wound as the plug is inserted into the fistula.

He sends the sample to Mayo Clinic’s Human Cell Therapy Lab, where a team led by Allan Dietz, Ph.D., co-director of the lab, proliferates the cells and embeds 20 million of them into a bio-absorbable plug. The work in the lab takes approximately six weeks.

Then, in another operation, Dr. Dozois inserts the plug into the fistula. He secures it in place by suturing the plug’s cap, which is on the inside end of the fistula, to the interior lining of the rectum.

A medical mystery

Exactly what happens next is something of a mystery, but Dr. Dietz believes the stem cells help to squelch inflammation in the area and draw other cells with healing properties to the wound. Mesenchymal stem cells also promote the growth of new blood vessels.

Calming inflammation in and around the fistula is necessary to allow the body’s normal healing process to begin, Dr. Dietz says. Sending mesenchymal stem cells to get to work in an open wound is just what the body would do on its own, if things had not been thrown off kilter by Crohn’s disease.

Research teams at other institutions have attempted to treat fistulae with mesenchymal stem cells, but the approaches have varied. One notable example is that of scientists in Europe who take stem cells provided by donors and inject them into patients’ fistulae. This seems to work for about half of the patients, notes Dr. Faubion.

The Mayo scientists questioned the effectiveness of delivering the cells in this manner.

“Were the cells really getting to the tissue that was at risk, or where they needed to be, by these somewhat blind injections?” Dr. Dozois wondered.

Together, the researchers brainstormed the strategy of implanting a patient’s own stem cells into a fistula plug. So far, this method of delivery seems to be working quite well. Though the trial is ongoing, Drs. Faubion, Dozois and Dietz believe they’re really on to something.

They recently submitted a manuscript containing data on patients’ six-month follow-up results.

“We’re enthusiastic enough about the results that we are in the planning stages of a larger phase II trial,” Dr. Faubion explains. “So we’re pretty happy with the way things have been going.”

In addition, they have permission from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to use this protocol experimentally for people who suffer from a condition called cryptoglandular fistulizing disease and for children with Crohn’s-related fistulae. Dr. Faubion holds board certifications in both gastroenterology and pediatric gastroenterology.

The group currently is seeking approval to test the use of the stem-cell-studded plug in people who develop fistulae following serious gastrointestinal surgery.

“I think there’s obvious early implications to treating fistulizing disease,” Dr. Faubion says. “If it continues to work as well as it is, it’s going to be first-line therapy, I think. Plus, it’s not an immunosuppressive agent, so it’s going to be first-line therapy for people with fistulae.”

Taking on Crohn's

As exciting as the team’s early findings are, the researchers ultimately have their sights set on using mesenchymal stem cells in a much bigger way for Crohn’s patients. Given time and adequate funding, they hope to develop a way to employ stem cell therapy to address Crohn’s disease as a whole.

“I would envision a program from Mayo that we apply the cells in a localized fashion,” explains Dr. Faubion, “where the patient needs that, rather than just a generalized, systemic fashion.”

Dr. Dietz has some experience with such approaches. His laboratory cultivates stem cells for use in several different trials, including ones for people suffering from extreme osteoarthritis, renal stenosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (better known as Lou Gehrig’s disease) and other nervous system disorders.

He likens the stem cells to medication.

“We potentially have a very powerful anti-inflammatory agent,” he says. “With osteoarthritic knee, think of steroids. This could be as useful as a steroid, but way more directed, right? Because you’re going to get the entire dose right at the point of the damage.”

This knowledge of stem cell therapy, combined with Dr. Faubion’s experience treating Crohn’s patients and Dr. Dozois’ skill in colorectal surgery, make the trio a powerful lineup in the fight against Crohn’s disease. And that is exactly what patients need.

“A project like ours, for example, you can’t do unless you have this kind of expertise and the collaborative approach that we’ve taken,” Dr. Dozois says. “So I think we’re furthering the science much faster and much better because we’re doing it through collaboration, versus individuals doing it themselves.”

- Laura Mize