-

Biotherapeutics

Discovery’s Edge: Serving where needed

Engineer, Air Force brigadier general, and surgeon: Michael Yaszemski, M.D., Ph.D., builds research teams and polymer scaffolds to regenerate hope for patients.

Orthopedic surgeon Michael Yaszemski, M.D., Ph.D., dressed in his scrubs, glanced through the window to the operating room. The patient lay unconscious on the table, draped and ready for the doctor to begin surgery. But at that moment an odd sensation passed through Dr. Yaszemski’s head, unlike anything he had ever experienced.

“I suddenly became aware that something bad had happened inside my head,” Dr. Yaszemski recalls now, 10 years later. “I turned around, I told one of the colleagues, ‘I’m in trouble. I need help right now.’”

Dr. Yaszemski passed in and out of consciousness during the next two days. He recalls a priest performing last rites at his bedside. He had suffered a brain hemorrhage, of unknown cause. The doctors who operated on him told him mortality for that kind of event is 50 percent.

“I flipped a coin and it stayed up on the living side,” Dr. Yaszemski says. “Anytime I feel my temper want to rise, I just think about the day I said goodbye to my wife and got the last rites. All of a sudden what I have in front of me doesn’t seem like too much of a problem. Nothing bothers me anymore.”

Surviving, Thriving

While his equanimity and humility are Dr. Yaszemski’s hallmark among his surgical staff and research colleagues, they’ve also helped him be a part of and lead high-functioning medical teams. A nationally renowned spinal surgeon, chemical engineer, and retired Air Force brigadier general, he is a widely-published researcher in the fast-evolving field of regenerative medicine. And he was recently elected to the prestigious National Academy of Medicine.

“His leadership abilities kind of naturally come through in settings where he is able to effectively cross-collaborate, get people to work as a team and do that in the interest of promoting the best care for his patients,” says Dr. Mark Pagnano, M.D., Mayo’s chair of orthopedics. “Dr. Yaszemski is definitely someone who knows how to build an effective team. He’s demonstrated that in the surgical arena and in the research arena as well.”

Surgeon, Engineer

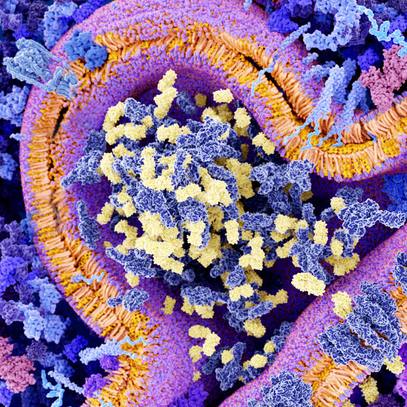

Dr. Yaszemski spends roughly half his time as an orthopedic surgeon, and the other half as a researcher in regenerative medicine, a discipline directed to helping the body to heal itself. As director of the Tissue Engineering and Biomaterial Laboratory, he supervises 16 researchers, students and technicians as they design polymer scaffolds.

These scaffolds provide a base and guide to encourage the regrowth of bone, nerves, and cartilage to repair a severe injury from an accident or illness such as cancer. It’s hoped that regenerative tissue growth will reduce the need for metal splints to stabilize the spine and allow for the regrowth of nerves to restore feeling and function.

“You can design a polymer to do many different things,” says Dr. Yaszemski.

He explains that the scaffolds may be formulated to be strong and rigid, providing a platform for the regrowth of bone. The polymers may also be injected as a liquid and then harden to fill a cavity. Tubular scaffolds that look like a flexible drinking straw can guide the regrowth of nerve cells and then biodegrade. And to encourage cell growth, polymers may be embedded with minerals or biological molecules or even with an electric charge.

“It’s all about the cells,” he says. “The goal here is to make a scaffold that will attract and have these cells anchored to it and give them the signals they need to start making the tissue you want them to make.”

Dr. Yaszemski learned much of what he knows about polymers before he ever imagined a medical career. “I never thought in my wildest dreams that 40 years later I’d be making polymers to put into people.”

His journey into medicine remains something of a mystery, even to him.

Decisions, Decisions

Son of a New York police officer, Dr. Yaszemski grew up in New Jersey and graduated from Lehigh University with a bachelor’s in chemistry. He entered graduate school on an NCAA  scholarship — for which his college football coach had applied on his behalf without Dr. Yaszemski’s knowledge. “This,” he says, “was one of those unexpected opportunities.”

scholarship — for which his college football coach had applied on his behalf without Dr. Yaszemski’s knowledge. “This,” he says, “was one of those unexpected opportunities.”

As a master’s student, he produced polymers as part of an antibody drug complex. “Of course, I didn’t have the slightest idea of what medicine was about. Maybe that got me interested. I don’t know. It was nothing I planned for,” he says.

Nonetheless, after his master’s, he went to work for the roofing manufacturer GAF Corp. “I was happy being an engineer,” he says. He was married, and his wife entered Georgetown Law School. “For reasons I don’t understand 40 years later, I sent an application into one school, Georgetown Medical School, and got in. Maybe I just wanted to be with my new wife.”

His uncle, in the Air Force, called. Dr. Yaszemski recalls the conversation like this: “Nephew, congratulations. I hear you got into medical school. How are you paying for it? I know you and your wife can’t afford it, and your parents can’t afford it. We’ve got this new program in the Air Force called Health Professions Scholarship Program. I’ve taken the liberty of getting an application and mailing it to you. I suggest you read it, fill it out, and send it in.” The Air Force paid for medical school.

Engineer, Surgeon, General... And More

“Once I got in I was hooked,” Dr. Yaszemski says. “This commitment to service, this commitment to excellence, and this insistence on integrity rang a bell with me that I never thought would be part of the military.”

Stationed at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, he became a surgeon while also earning a Ph.D.

Dr. Yaszemski left active duty and was recruited by Mayo Clinic in 1996. He remained in the reserves, performing surgery in tent hospitals during tours at Balad Air Base in Iraq and Bagram Airfield in Afghanistan in 2005 and 2006.

Anthony Windebank, M.D., a Mayo Clinic neurologist working with Dr. Yaszemski says the lessons of war added to Dr. Yaszemski's abilities. “Seeing young people with severe limb damage from bullets that conventional techniques can’t repair drives part of his desire to ask what can we do better to serve these young people. I think the other way it contributes to his medical career is that he is incredibly well organized in terms of getting people to do what needs to be done to get the job done. He strongly believes the team works best when the team works together.”

Despite his achievements, Dr. Yaszemski continues to be known for his soft-spoken humility. He often avers that each of us is replaceable.

When he was read the last rites ten years ago and whisked from the operating room to an emergency room as a patient, the other surgeons had to decide what to do with the patient who was already prepped and anesthetized. After consulting with the patient’s family, another surgeon stepped in to complete the operation. And that’s how it should be according to Dr. Yaszemski.

“We are all expendable—in a second,” says Dr. Yaszemski. “We go away, and if the job we’re doing is an important job, someone else will be doing it.”

- Greg Breining, August 8, 2017

| Developing polymers for bone, nerve grafts

Lichun Lu, Ph.D., a Mayo Clinic bioengineer, is developing polymers – multiple- The team has come up with a pair of polymers that, when placed around a damaged vertebra, grow to be just the right size and shape to support the spinal column. To use the polymers, a surgeon would open a sterile package holding a tiny hollow tube made of an absorbent, biodegradable polymer (a hydrogel), place it within the spinal column and then douse it in saline for about five minutes, tweaking its position as it expands to bridge the gap left by a missing piece of vertebra. Next, the tube-shaped mold would be filled with a second polymer, an injectable bone cement. “This material is much stronger, and it can be engineered either to stay in place indefinitely, or to be seeded with cells and growth factors [to help bones regenerate] and to biodegrade over time, ” explains Dr. Lu. Electrical charge has a significant effect on growing nerves, so Dr. Lu is partnering with Anthony Windebank, M.D., to create positively charged hydrogels for conduits that stimulate and guide neuroregeneration in the body.  In collaboration with Andre Terzic, M.D., Ph.D., and others, she is strengthening these conduits for neural tissue engineering by embedding them with carbon graphene, a material stronger than steel. And in a multiteam effort to help patients with severed spinal cords, Dr. Lu is working with Dr. Yaszemski to build scaffolds that work with the strengthened conduits. These scaffolds will be seeded with cells, growth factors, and drug-releasing microspheres, made out of yet another new polymer. |

Setting the stage for new treatments  Alexandra Greenberg, Ph.D., is a scientific casting director. She helps turn discoveries into new treatments by connecting the people, ideas and processes within the Biomaterials and Biomolecules Facility to other centers at Mayo Clinic.The facility brings together physicians, researchers, engineers and technicians to create and manufacture unique materials and devices to advance therapy for unmet patient needs.This is translational medicine: improving health by turning discoveries into new treatments.Potential therapies are first studied in the lab. Then, if proven safe and feasible, they move to clinical trials, and Dr. Greenberg helps make this happen. With her understanding of the science and regulatory requirements, she seeks to prevent wasted time and resources by helping Mayo innovators navigate the often-convoluted path to an approved new treatment.Dr. Greenberg is part of the Mayo Clinic Center for Regenerative Medicine. She coordinates with Mayo’s Center for Clinical and Translational Science and Center for Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation, part of the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery. By finding and casting the correct actors, Dr. Greenberg helps the centers function better and bring innovative care to patients faster. Alexandra Greenberg, Ph.D., is a scientific casting director. She helps turn discoveries into new treatments by connecting the people, ideas and processes within the Biomaterials and Biomolecules Facility to other centers at Mayo Clinic.The facility brings together physicians, researchers, engineers and technicians to create and manufacture unique materials and devices to advance therapy for unmet patient needs.This is translational medicine: improving health by turning discoveries into new treatments.Potential therapies are first studied in the lab. Then, if proven safe and feasible, they move to clinical trials, and Dr. Greenberg helps make this happen. With her understanding of the science and regulatory requirements, she seeks to prevent wasted time and resources by helping Mayo innovators navigate the often-convoluted path to an approved new treatment.Dr. Greenberg is part of the Mayo Clinic Center for Regenerative Medicine. She coordinates with Mayo’s Center for Clinical and Translational Science and Center for Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation, part of the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery. By finding and casting the correct actors, Dr. Greenberg helps the centers function better and bring innovative care to patients faster. |